Criticism of one's work is very hard to take. Your dissertation or manuscript represents your best efforts--blood, sweat, and tears. To see it shredded by another is embarrassing and depressing. However, as scientists and authors we must learn to accept and deal with criticism, constructive or not. Everyone goes through a maturation process in this regard. So I thought it would be interesting to describe the various stages through which a scientist evolves (or may evolve--some get stuck at an early stage for their entire careers).

The next series of essays is based mostly on my own and colleagues' experiences--our reactions to criticism as well as reactions of others to our criticism (i.e., essentially anecdotal and not necessarily representative of all scientists).

Today's post focuses on the first of three stages in dealing with criticism:

Early Career (e.g., student and post-doc)

This stage is typically characterized by extreme sensitivity to criticism. Novices may be dismayed and become extremely discouraged when faced with the news that their work is not acceptable. People at this stage of development sometimes view critical remarks as personal attacks--they assume that the people who are criticizing their work and their writing are trying to "put down" or "hold back" the budding scientist and author. Another belief is that the critic is jealous and is being over-zealous as a consequence. Novices sometimes believe that their writing is just fine, if not brilliant, and look upon suggestions for improvement with a sense of disbelief or disgust. They may balk at making suggested changes and strive to ignore editorial suggestions.

The novice author is reluctant to amputate any verbiage, extraneous or not, because every sentence reflects great effort--not unlike passing kidney stones. The writing also may be sprinkled with numerous citations, but many of them do not actually support the point being made--the novice having failed to check the original citations and is simply repeating what has been said by others. A table may add little to the paper and will take up valuable journal space, but the novice writer is loathe to remove it because it represents numerous, tedious measurements and shows how hard they worked. Figures fail to effectively depict the data in a way that conveys the essence of the main research findings (e.g., there is no distinction made between the most important results and the merely ancillary data). However, the novice balks at removing incidental figures for the same reason stated previously for tables. Finally, the novice author has worked very hard to write dense, convoluted sentences that can only be comprehended with repeated readings--in the belief that this writing style conveys sophisticated mastery of the topic.

Unfortunately, the inexperienced writer is often resistant at this stage to recommendations and wishes to avoid the idea that their best efforts are not good enough. By ignoring critical remarks, they can more easily protect their fragile egos and especially circumvent the additional work involved in revision. Such actions are sometimes grounded in the belief that the criticisms by the adviser are frivolous and random and therefore can be justifiably ignored. In other cases, the novice believes that the advice is based solely on a difference of opinion, and both opinions (novice and adviser) are equally valid--in which case, the novice prefers his/her own.

Little wonder that the early-career writer is reluctant to listen to suggestions for revision.

Young scientists who are in this frame of mind sometimes will return their "revised" thesis or manuscript with few or none of the suggested changes, thinking that their adviser will not notice or will forget their original criticisms. This rarely works because the adviser will identify the same or additional flaws during the second read. Novice writers invariably make the same types of mistakes, of which they are often unaware, but which jump out at an experienced reviewer or editor like slimy toads popping off the page.

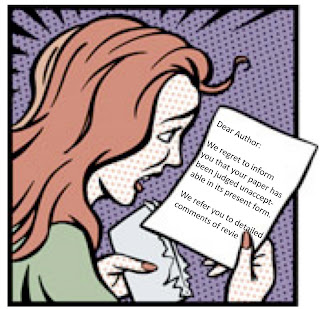

Sometimes, the budding scientist will further ignore their adviser's assessment regarding the raw, unrefined nature of their masterpiece and without permission, go ahead and submit the manuscript to a journal. This action is typically followed by swift rejection accompanied by excoriating comments of reviewers (if it is even sent out for review). If by some miracle the paper is accepted with major revision (the reviewers having taken pity on what is clearly a student's first paper), the novice ignores the reviewer comments and returns the manuscript to the journal with only a few minor changes, upon which the editor quickly rejects it.

In a few cases, the novice author, having graduated or found employment elsewhere, removes the adviser's name from the paper prior to journal submission in the mistaken belief that this will absolve the need to address requested changes. The manuscript is subsequently sent to the adviser for review, since she is the acknowledged expert in the field. This unfortunate turn of events is followed by a reality check administered by both the journal editor and the adviser.

Some of the descriptions I've painted here are extreme scenarios, but are based on real events. A few of these early career reactions have been repeated enough times to suggest a pattern among novice authors. I think most advisers, reviewers, and editors, however, understand the mindset of novices. We are not unsympathetic, because we've been there ourselves. However we also know that it is extremely challenging to be successful in the competitive world of scientific research. Therefore, we know that improvement only comes with criticism--and deliberate effort on the part of the novice to address their weaknesses.

Some people pass through this stage quickly; some more slowly; and a few find themselves stuck here indefinitely. It's up to the individual to transition to the next stage in dealing with criticism: Mid-Career (see next post).

1 comment:

As a novice (finishing PhD student), I would like to add that I do not identify personally with the reaction to criticism that you have described. I do not deny that this reaction is rampant, however. My reaction, along with a few of my women colleagues with women advisors (anecdotally), is to beat ourselves up about not writing a better draft, manuscript, etc. in the first place. We often flinch instinctually in anticipation of criticism. To remedy this fear, every time I submit a draft to my advisor or committee, I remind myself that the product of this review is a better paper. And each time I am learning to write more effectively. I have found this to be an essential practice for my transition from the reliance on external encouragement to internal motivation.

Post a Comment