In the last post, I promised a review of the four most common forms of gender bias.

In this post, I will cover number 1: Prove It Again. In this type of bias, women working in traditionally male professions (e.g., STEM fields) must prove their competence repeatedly to maintain their credibility while men are presumed to be competent. If a man makes a mistake, it's more likely to be viewed as not representative of overall ability, whereas a woman's mistake is never forgotten and trotted out whenever she is compared to her male colleagues. Sound familiar?

This double standard is likely one of the factors causing those statistics showing that women must work several times harder and produce more than male counterparts simply to be acknowledged as competent. This has certainly been my experience throughout my career. I've observed male scientists, with few accomplishments, be described as "having great potential"and rewarded based on that belief, while highly competent female scientists with a long list of real accomplishments were overlooked.

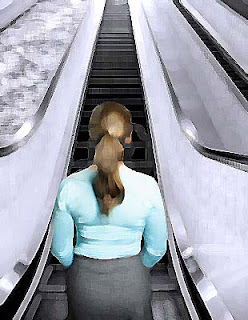

Earlier in my career, this bias was certainly in evidence. I often felt as if I was running up a down escalator, working harder and harder to reach the top; if I paused, I would be carried backwards. I saw male colleagues with less experience and fewer accomplishments being offered more responsibility, higher level positions, and better opportunities to work on (or lead) research projects. They were on the up-escalator. Some were actively climbing, while others were just standing; but all could move up, even with no effort.

The few times I complained, I was told that "Joe" was being promoted because he showed "potential". In one job, when I asked for a raise or promotion, I was always told that I would be recommended, but only after I had accomplished a specific task--usually something that my supervisor figured I would never be able to do (conduct a difficult study and get a paper published reporting the results within a certain time-frame). When I came back with that task completed, I was given what I had been promised, but the delay was sometimes as long as a year. I was too young and naive to realize what was happening. I just assumed that my performance was somehow lacking, and these extra requirements were necessary to prove my capabilities to superiors. I eventually realized that male counterparts were not required to jump through the same hoops (I asked them).

I doubt that my superiors (male) were consciously biased, because I was encouraged to develop as a scientist. Whatever I had accomplished in the past, however, was apparently not enough to be viewed as showing "potential" (much less having achieved that potential). They just seemed to need additional evidence of my capability--no matter what I had accomplished in the past.

I realize now that part of this perception was due to the fact that I did not "promote" myself by talking about my accomplishments or making sure that my skills were widely known. I've discussed the topic of bragging in previous posts and the influence it can have on one's career. It's particularly difficult for women, who are typically expected to be modest, to self-promote successfully. I'm not sure it would have worked for me, and possibly could have backfired--at least at that time and at that stage in my career.

For more on gender bias patterns, see the Gender Bias Learning Project. The next post will talk about the choice women must make between being liked but not respected and being respected but not liked.

1 comment:

Really excellent post. All of it sounds so familiar. And yes when women are told to brag I wonder whether that would actually help them or hurt them. We know women are told that they don't negotiate enough but then looked upon negatively when they do.

Post a Comment